Subscribers of SWL’s weekly newsletter now have a chance to download a map of Ribera del Duero for free (Those who haven’t signed up yet may do so on the right-hand navigator of our homepage).

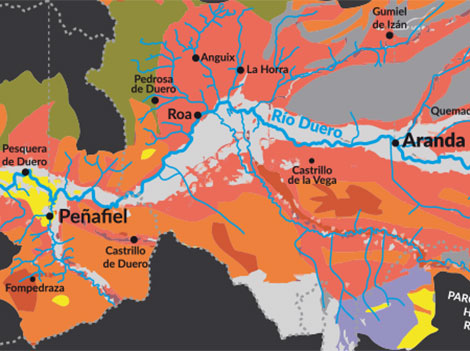

We are particularly grateful to Pablo Rubio, manager of PSI, Peter Sisseck’s second project in Ribera del Duero, for all the information and help provided for the presentation. Graphic designer Luis Munilla assembled all the pieces to highlight basic aspects (soils, geography, figures) and provide a better understanding of the region.

Following Peter Sisseck’s idea of making a red wine reflecting the region’s tradition (PSI), Pablo embarked on a research and mapping project to identify historical locations of vineyards in Ribera del Duero. A considerable amount of the extensive information on soils and landforms handled by Pablo has been shared with the Regulatory Board. A study of soils done by Vicente Sotés, professor of viticulture in the Agricultural Production Department at Madrid’s Polytechnic University (UPM) and Vicente Gómez-Miguel, associate professor of edaphology, climate and geology, was already in possession of the DO and Sisseck chairs a commission to view the possibility of redefining vineyard designations in the DO.

Obviously, our map is a simplified version. We have tried to make it as eye-catching and informative as possible, but this text adds more facts and context.

Origins and geography

Ribera del Duero is a sedimentary valley. A series of geological layers emerged after the river eroded the original bedrock. Erosion continued to affect these layers which were gradually filled with sedimentary fluvial materials. The landforms that resulted from this process include alluvial plains (old terraces of rivers that have remained at high altitude), foothills (areas with rocky materials that have rolled down), terraces (modern materials near the river) and moorland (high areas that formed part of the original bedrock).

According to Pablo Rubio, “the complexity of soils in Ribera is a sum of the materials that have filled the area, the high terraces, the mountain erosion and the continuous or intermittent waterways found specially in the regions of Burgos, Soria and Segovia.”

To show this complexity, we have drawn a map of soils with cross-sections showing major variations in different areas of the Duero valley. Broadly speaking, they coincide with the boundaries of the DO’s three main provinces: Soria, Burgos and Valladolid.

Three provinces, three identities

Valladolid. Barely 5 km wide, this area is the narrowest part of the valley as it ascends sharply towards the moorland on its northern and southern sides. The orography resembles the original terrain thus showing less soil complexity. This stretch of land includes terraces on the river Duero, slopes climbing to the moorland and the flat moorland itself. A few top estates like Vega Sicilia, Hacienda Monasterio, Finca Villacreces or Arzuaga are located in this area.

Burgos. The valley widens considerably here and the erosive action of water has brought layers to the surface. These layers also appear in Valladolid, where they have no incidence in wine growing as they lie low, out of the reach of roots. In Burgos, the number of water courses and Duero tributaries, particularly on its right bank, is significantly higher. As shown in the Aranda de Duero axis, water has removed a great deal of its original materials leaving complex soils that include Duero terraces, ancient terraces at higher altitude, slopes with a variety of materials and limestone outcrops on the highest, erosion-resistant areas of the moorland.

Soria. The valley narrows again here. From San Esteban de Gormaz there is a steep climb to the Sierra del Rey mountain on the south, but the north has complex soils, similar to those found in Burgos. The main difference is the altitude: San Esteban de Gormaz lies at 854m, compared to Valbuena del Duero (730m) and Aranda de Duero (730m). This creates a different soil composition —reddish silt as opposed to the dominant sandy conglomerates around Aranda.

Understanding Ribera del Duero: key elements

Altitude and exposure have traditionally conditioned grape ripening in the area, yet climate change is altering this as more producers look for cooler areas.

Compared to Rioja, its alter ego in terms of premium reds, average altitude is much higher in Ribera (around 800m on the plateau as opposed to 400m in Rioja) which somehow compensates for its southernmost latitude. This location means more extreme weather with higher risk of frosts in spring and early autumn –less usual in other winegrowing regions– on the latest stages of ripening and harvesting. Heat retention is not as high as in Rioja forcing the plant (mainly Tempranillo as well as some Cabernet and Merlot) to ripen the fruit in a shorter period of time hence the difficulties in cool vintages like 2007, 2008 and 2013.

Vineyard evolution

Following the tremendous success of Ribera reds, the region has experienced a meteoric rise since the late 1980s. This fact is usually backed with data showing the growth in the number of wineries and surface under vine, but we think there are other factors that explain this evolution. All data have been sourced from the region’s Regulatory Board.

Vineyard age. Of the 22,300Ha under vine in Ribera del Duero nowadays, 14,500 were planted after 1990.

|

HOW

OLD VINEYARDS ARE |

||

|

Year of

planting |

Surface (Ha) |

% Total |

|

Prior

to 1900 |

317.55 |

1.42% |

|

Between

1901 and 1910 |

106.4 |

0.48% |

|

Between

1911 and 1920 |

398.9 |

1.79% |

|

Between

1921 and 1930 |

769.61 |

3.45% |

|

Between

1931 and 1940 |

1,103.20 |

4.94% |

|

Between

1941 and 1950 |

1,701.88 |

7.63% |

|

Between

1951 and 1960 |

888.7 |

3.98% |

|

Between

1961 and 1970 |

548.21 |

2.46% |

|

Between

1971 and 1980 |

149.34 |

0.67% |

|

Between

1981 and 1990 |

1,761.34 |

7.89% |

|

Between

1991 and 2000 |

8,100.32 |

36.29% |

|

Between

2001 and 2010 |

5,358.58 |

2.01% |

|

Between 2011 and 2014 |

1,115.54 |

5.00% |

|

Total |

22,319.57 |

100% |

In terms of plantings preceding the foundation of the DO in 1982 (just over 7,000Ha, according to data supplied by the Regulatory Board), Pablo Rubio estimates that only around 3,000Ha are usable. “The rest has either been uprooted as a result of land consolidation or has not been properly looked after and has many plants missing; these lands are unlikely to be profitable or capable of producing quality fruit,” he points out.

Rubio estimates that between 1999 and 2014 almost two thirds of Ribera del Duero’s old vineyards have been lost. “Given that prices are the same for old and young vines, there aren’t really any wine growers working these old vines in a professional way,” he explains. From a purely practical point of view, machines can only be used on new plantings with lanes between vines ranging from 2.5 to 3 metres compared to 1.7-2m in old vineyards.

Grape varieties. Tempranillo has always ruled in Ribera del Duero, but its increasing dominance has displaced other minor grapes. In 1997, Tempranillo accounted for 77% of the surface under vine, with other local varieties like Albillo and Garnacha holding 21% and international varieties (Cabernet, Merlot, Malbec) a mere 2.1%. Tempranillo now covers 97% of the region’s surface under vine.

Vineyard location. As a result of massive plantings, the surface under vine on flat land has significantly increased and it now stands at 12% compared to 1% in 1989. This fact, together with the growing number of young vineyards, has brought higher average yields which nevertheless remain within accepted quality standards.

|

GRAPE PRODUCTION AND YIELDS |

||

|

Year |

Yields (Kg/Ha) |

Production (million Kg) |

|

1997 |

1,448 |

18 |

|

1998 |

2,681 |

34 |

|

1999 |

3,978 |

54 |

|

2000 |

4,495 |

63 |

|

2001 |

4,245 |

65 |

|

2002 |

2,816 |

49 |

|

2003 |

4,131 |

76 |

|

2004 |

3,879 |

75 |

|

2005 |

3,208 |

64 |

|

2006 |

4,98 |

97 |

|

2007 |

3,647 |

76 |

|

2008 |

3,361 |

70 |

|

2009 |

4,162 |

87 |

|

2010 |

3,383 |

71 |

|

2011 |

4,519 |

97 |

|

2012 |

3,992 |

86 |

|

2013 |

4,385 |

95 |

|

2014 |

5,565 |

122 |

Vineyard concentration in the western part of the appellation is significant. It extends across all the villages in the province of Valladolid and those in western Burgos up to Arroyo de San Miguel in the north (Anguix and Roa) and the river Riaza to the south (Fuentecén). In 1989 this area accounted for 22% of the total surface under vine; now it extends to 49% of the territory (see breakdown by provinces in the chart below).

|

WESTERN

RIBERA DEL DUERO |

|||

|

Province |

Surface (Ha) |

1989 |

2014 |

|

Valladolid |

4,466 |

4% |

21% |

|

Western Burgos |

5,988 |

18% |

28% |

|

TOTAL |

10,454 |

22% |

49% |

|

EASTERN

RIBERA DEL DUERO |

|||

|

Province |

Surface

(Ha) |

1989 |

2014 |

|

Eastern Burgos |

9,452 |

68% |

44% |

|

Segovia |

173 |

2% |

1% |

|

Soria |

1,269 |

8% |

6% |

|

TOTAL |

10,894 |

78% |

51% |

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers