Ojuel recovers supurao, a traditional sweet wine from Rioja

Ethnography brought Miguel Martínez to wine. A summer restoring the old snowfields in his village on the Moncalvillo mountains south of Logroño helped him to rediscover a plethora of nearly forgotten traditions.

Born and raised in Sojuela, Miguel directly experienced the exodus to urban areas of the 1980s in Spain. His parents, like many from their generation, moved to Logroño but partly to ensure a second income, partly for nostalgia, they kept the family’s vineyards.

“This is the reason why many 60+-year-old vines have survived —their potential is huge," explains this enthusiastic 32-year-old who sees wine as a vehicle to express the local culture, landscapes and traditions.

The value of tradition

That summer of 2005 changed Miguel’s life. His work was anything but easy. "Nobody wanted to replace the old stones in the snowfields up on the mountain when you could earn good money with the real estate boom", he recalls. But the experience provided him a comprehensive vision of the local history and traditions. Ice was a precious resource both to preserve food and for therapeutic uses and the snowfields, built at the end of the 16th century, are a testimony of the role of Sierra de Moncalvillo in providing supplies for Logroño.

Over those weeks Miguel learnt a great deal about the place where he was born. “Mount climbing was popular among the locals and many of them told me their stories." One of these was about supurao, a sweet wine made from dehydrated grapes that was an invigorating drink to work the fields or pick grapes. "I realized that we didn’t have notable buildings or a great cathedral in Sojuela; our greatest asset was tradition,” Miguel explains.

When he was a young child, he recalls seeing at his grandparents’ haystack the hanging grape bunches next to the homemade chorizo. “My grandfather’s sisters used to get together to make a sweet wine from those dried grapes; they never let me try them,” Miguel says. Supurao was also made when a baby girl was born —tradition dictated that the wine had to be cellared until the day of her wedding.

Their young wine —and their neighbours’— was made collectively in Sojuela’s old cellars. "Neighbours joined forces to fill the wine press and then again 15 days later to press the wine which was then distributed among them,” Miguel says. “With the must they made arrope, a kind of syrup served at breakfast or used as sugar in rosquillas, a doughnut-shaped biscuit. And the so called poor people’s nougat was a mix of arrope and almonds.” Miguel is now striving to recover many of these traditions.

The wine of the people

Supurao, in particular, became a bit of an obsession for him. In 2009 Miguel tried to make a late-harvest version of this sweet wine but it didn’t work as expected; most of the grapes either rot on the vine or were eaten by wild animals. His grandfather brought him back to reality: “Don’t change things; if you want to make supurao, do it like it has always been made.”

In some respects, the supurao was the women’s wine. They took it upon themselves to go to the vineyards and choose the finest bunches for their sweet wines. Now Miguel picks up the grapes for supurao around two weeks before the start of the harvest. “The skin of the grapes must be hard and smooth to withstand their transport and handling while hanging them–acidity is also a key factor,” he explains.

It takes Miguel almost two weeks to hang all the grape bunches. At first, he laid them on the floor but he needed more space and the process of dehydration wasn’t homogeneous, so he built a supporting wood frame with strings to hang the grapes and concentrate sugars. He usually keeps them there until mid-January but as the 2017 vintage came early, the grapes were dry by mid-November. A comparative with the previous harvest is particularly striking: the same number of grape bunches produced 6,000 kilos in 2016 but only 4,800 in 2017.

“The first week is crucial. We really benefit from the high altitude climate. No matter how careful you handle the grapes, some of the skins break but we open the windows on both sides of the haystack and the grapes quickly dry up.” The dehydration process entails some suppuration (“the grape skin has a sweaty, shiny appearance”), which explains the name of the wine, Miguel explains.

Fruit-driven and easy to drink

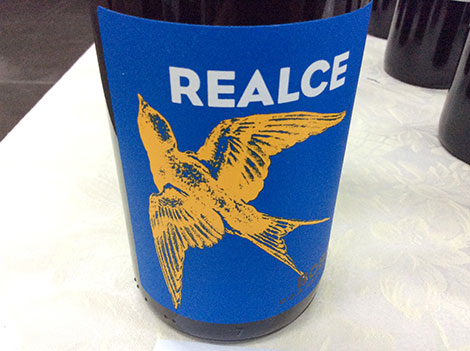

The first supurao to hit the market was made in the 2012 harvest but it couldn’t carry the Rioja seal or the vintage date because at the time, the Regulatory Board regulations didn’t contemplate sweet wines made from dried grapes. As the village name could not appear on the label, Miguel decided to call the wine Ojuel, which is nothing but Sojuela without its first and last letter. Two years later, the style was accepted by the Rioja Board.

Production is very limited to 600 litres of red and 400 litres of white. He started by blending red and white grapes but Miguel is more orthodox now. Supurao has traditionally been red, says Miguel, which is why he has decided to work the white grapes separately.

In terms of style, it’s a far cry from other classic, rich, concentrated Mediterranean sweet wines. Supurao is a naturally sweet wine with no added alcohol. Light coloured and light bodied, alcohol can vary from 11% to 12% vol. and sugar content can reach 180-190g per litre. The wine is barrel-aged for a very short time: after pressing the grapes with the aid of mats, partial fermentation takes place in stainless steel tanks, then the wine spends a couple of months in barrels prior to bottling. “In the old days, supurao was made in pitchers with no oak at all,” Miguel says. The red version can be compared to a fruit-driven, young wine with clean, defined red fruit and strawberry candy aromas. It’s a straightforward, easy to drink wine.

Old, modest winery and cellar

Small quantities of all the supurao wines he has made so far are stored in 64-, 110- and 225-litre barrels in the old family cellar, at the other end of the village from his winery. One of the whites we tasted was particularly striking as it had developed a complex, oxidative character.

The cellar, which seems to have remained untouched over the years, provides an unexpected time travel. The space is so cramped that Miguel has been digging —by hand— the walls to make space for this year’s barrels. His only aid is a pick and a shovel, like in the old days.

He also uses the old wine press (“made with gravel from the Daroca river,” he adds) to make a “cosechero” style, foot-trodden red. This simple, fruit-driven, delicious wine has been named Aloja (but written Aloxa with an X, in the ancient way) after an old beverage that used to be made by blending the ice from the snowfields with herbs.

It takes a lot of courage to work in such modest places. The haystack, which looks like it hasn’t changed much since Miguel’s grandparents used it, is perhaps a little larger. The upper part is exclusively destined to drying grapes for the sweet wines, which doesn’t leave much room below to store barrels, bottles, labels...

Other than the sweet wines, Miguel’s portfolio tries to highlight the distinctive character of this high altitude, mountainous area where small plots surrounded by forests still can be found.

Miguel works 9Ha distributed in 30 different plots at 550m to 800m above sea level. Grape varieties include red Tempranillo, Mazuelo and Maturana and white Viura, White Garnacha and White Tempranillo. With some single-vineyard wines about to reach the market, he also makes Ojuel Salvaje, a sulfite-free wine which is sold almost exclusively in Venta Moncalvillo, the Michelin-starred restaurant nearby where the Echapresto brothers champion traditional products and producers of Sierra de Moncalvillo.

Miguel is equally enthusiastic about the supurao, the restoration of the porch of Sojuela’s church, the opening of the hiking route leading to the old snowfields or the group that organizes regular hikes to identify the local flora and fauna with special attention to butterflies –the area concentrates 75% of the existing species in La Rioja and almost half of those found in Spain. Not surprisingly, butterflies are present in the renewed, attractive Ojuel labels —as you may have already guessed, Oxuel is written with an "x".

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers